I live in Cumbria these days but I still work in Dorset a few times a year. I have been thatching there for over thirty years, caring for roofs in and around Sturminster Newton, Shaftesbury and Gillingham. I learned in the early nineties using water reed, and then progressed to wheat reed. I’ve worked with both kinds of reeds and on all sorts of roofs, but it is when using wheat to re-thatch old Dorset cottages that I now feel best pleased with my work.

Southern England is the only place in Europe where straw is still grown regularly for thatching and where the farming and roofing skills still survive to use it properly for this purpose. The local District Council are unwilling to see the craft die out. It is the traditional form of thatching in many areas of southern England, sympathetic both to the ancient roof structures and to the countryside around. Thatching in wheat often gives the building a softer look, more rounded over the gables and eaves, more at home here in the West Country, where cereals have been grown for centuries. I am happy to contribute to Dorset’s wheat reed thatching heritage, but some of my fellow-thatchers have long disagreed with planning restrictions that prevent them from choosing which reed to use on listed buildings. A few of them have been very active in promoting imported water reed and claiming its superiority, while others may be unwilling to spend the extra time and attention that wheat reed demands from the thatcher, both on the ladder and in securing good-quality supplies.

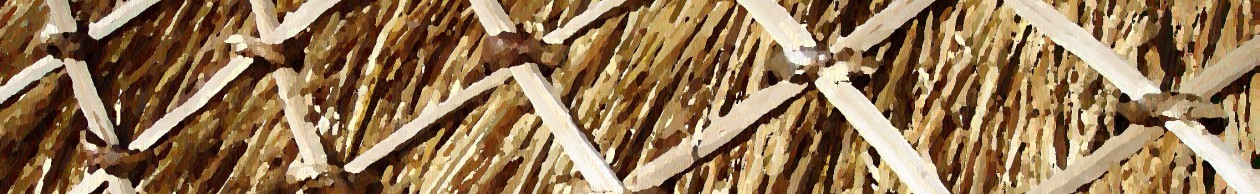

A tall, hollow-stemmed winter wheat is used for thatching. Once it was a by-product of the main seed crop, but now the older varieties are grown mostly for thatching. It is harvested with a binder and stood to dry in the field in stooks before being stacked carefully into ricks. When the threshing machine arrives, the grain, weeds and leaf are removed, leaving the straw largely unbruised. The bundles are now known as combed wheat reed.

Wheat reed is attached to the roof by twisted hazel pegs (spars) that are driven into an undercoat like staples, leaving the old rafters undisturbed. This type of thatch is light and gentle to the older structures.

While some thatchers are still willing to use spars to fix water reed to a thatch undercoat, I feel it is not always ideal for a number of reasons. First, it is asking a lot of an old base layer to hold so great a weight tightly on the roof. I have seen such roofs where the spar bonds have loosened over the years, possible through storm winds or insufficient attention when fixed, allowing reeds to drop and premature holes to develop. Secondly, I have known the sheer weight of water reed to cause a collapse in older structures; one only has to carry them across a site to appreciate how much heavier water reed is. Water reed is heavier and requires a stronger force to attach it to the roof, and the two kinds of thatch used in the county today are not always completely interchangeable.

I am not against the use of water reed at all; it can be a good and hard-wearing material and where the roof is made from sawn timber rafters, it is almost always the right choice, being fastened down with hooked nails (crooks) or with modern screws.

But the supposed trump card in the debate between the two most common types of thatch is the view that water reed will last much longer. When customers see a bundle of each material side by side, they notice the extra length of the water reed and are in the position of having to fork out many thousands of pounds and so are eager to hear a promise of forty, or fifty, years’ life. They are easily persuaded that the difference in length of the two materials is reflected directly in the longevity of the roof. As the ends of the reeds get wet, they rot. Over the decades, the decay moves back along the reeds to the place they were attached and the water can find a way in via the fixings. So, the longer a bundle of thatch looks, the more easily persuaded a customer often is that the coat work will last a long time. But this is not as simple as it sounds. It should be made clear that wheat reed is laid on the roof with more deeply buried fixings than water reed and extra length will count for nothing. Especially true if the read is not waxy and soaks in the moisture from the rain, speeding up decay.

All thatching materials are subject to huge variations in quality. In Tarrant Monkton I was sent by my old boss to re-ridge a cottage and found that the water reed on it had rotted out through capillary action after less than fifteen years, while in Shaftesbury I have found a combed wheat reed roof that was ready to do another ten-year stretch after 32 years’ service. While these are unusual examples they illustrate the variation in results. The potential life of a new thatch is dictated by a mix of many things. The roof pitch and its exposure to the weather, the simplicity of the roof design and the quality of the reed are all important, and of course the craftsmanship plays its part; a thatcher must ensure that the depth of the fixing is consistent and that the reed is laid with even pitch and density across the whole roof.

On average wheat reed will last 25 years if it is well grown and correctly laid, and there is no guarantee that water reed will do any better here in the wet climate of the West Country. The outrageous claims for its longevity being bandied around seem unfounded – echoes, perhaps, of stories from Norfolk, where the roofs are steeper and the climate colder and much drier.

I am convinced that combed wheat reed is perfectly suited to the old roofs of the west country, not out of a romantic or whimsical love of history and tradition, but because it is a viable and competitive material, perfectly suited to the task of protecting some of our oldest buildings and well able to hold its own over imported water reed.